Rigid vs Flexible Packaging: What Actually Works on Automated Food Lines

Most discussions around rigid vs flexible packaging get stuck in branding, sustainability, or consumer convenience. That framing is incomplete—and often misleading.

On an automated food line, packaging is not a marketing decision. It’s a production architecture decision with downstream consequences for throughput, labor, quality, uptime, and scalability. The wrong format rarely fails on day one. It fails quietly—when volumes increase, SKUs multiply, or automation tightens tolerances.

This guide reframes rigid packaging vs flexible packaging through the lens that actually matters: how each format behaves under automation.

Why Packaging Format Becomes a Problem During Automation

Manual or semi-manual operations hide weaknesses. Human hands compensate for instability, misalignment, and inconsistency.

Automation does not.

Once packaging is handled by conveyors, pick-and-place systems, fillers, and sealers, hidden issues surface fast:

- Deformation under acceleration, compression, or stacking

- Inconsistent sealing caused by timing, contamination, or heat variation

- Handling instability from unpredictable orientation or center of gravity

This is why “it works today” does not mean “it scales tomorrow.”

Automation removes forgiveness from the system. Packaging formats that tolerate manual variability often collapse under machine logic.

What “Rigid” and “Flexible” Mean in a Production Context

Forget dictionary definitions. In production, these formats are defined by how they move, seal, and survive on a line.

Rigid Packaging (from a line-design perspective)

Rigid packaging acts as its own mechanical carrier.

Operationally, this means:

- Structural stability under automated handling

- Predictable orientation on conveyors and star wheels

- Stackability before and after filling

- Consistent geometry at high speeds

Common rigid formats include cans, bottles, jars, tubs, and cups.

The tradeoff:

Rigid packaging brings tooling rigidity. Changeovers require physical parts, and footprints are larger due to container volume.

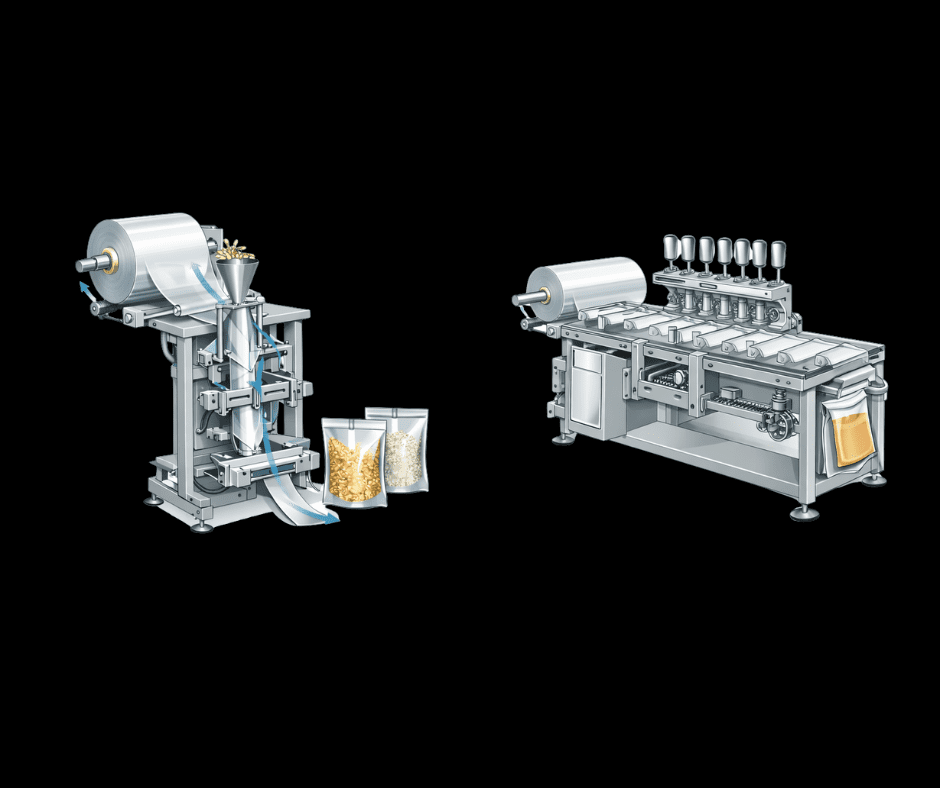

Flexible Packaging (from a line-design perspective)

Flexible packaging relies on material tension and process control, not structure.

Operationally, this means:

- Film-based formats (pouches, sachets, rollstock)

- Exceptional material efficiency and inbound logistics density

- Dependence on precise sealing parameters

- Sensitivity to speed, heat, tension, and cleanliness

Flexible formats are not self-supporting. They often require:

- Grippers, suction cups, or carriers

- Careful control of fill dynamics

- Tight synchronization across stations

The tradeoff:

Flexible packaging scales well in variety—but poorly in forgiveness. Small deviations cause leaks, mis-seals, or instability.

Throughput: Where Rigid and Flexible Behave Differently

This is the point where most content about rigid vs flexible packaging stops being useful.

On paper, both formats can claim impressive speeds. On an automated food line, however, throughput is not defined by peak machine ratings but by how predictably a package behaves under continuous motion. This is where rigid and flexible formats diverge sharply.

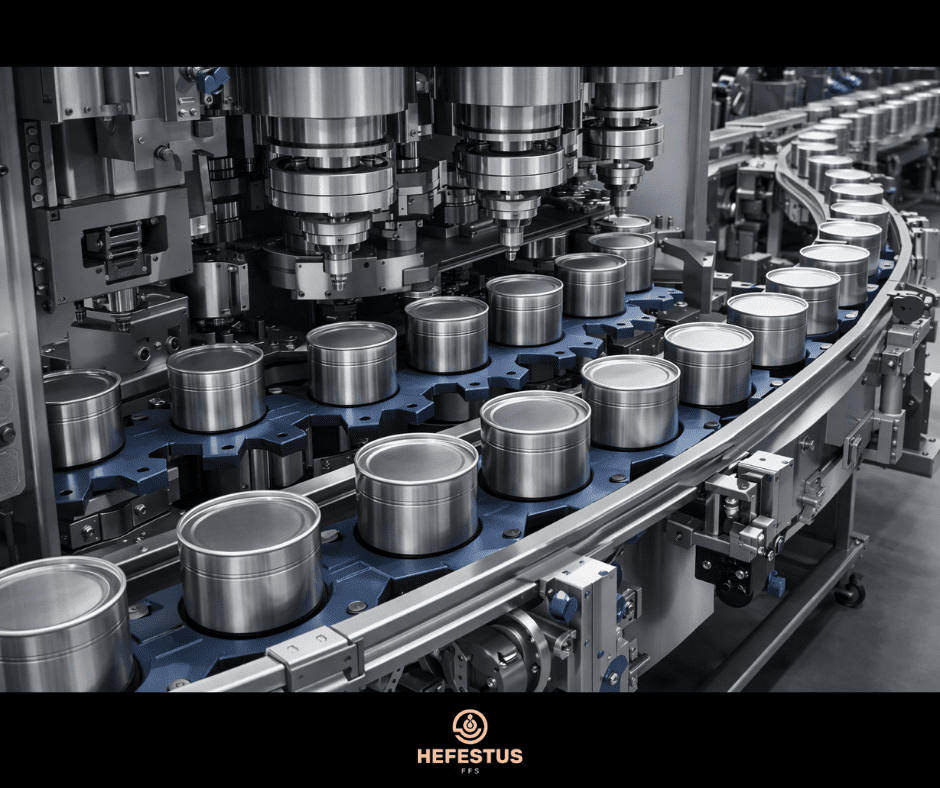

Speed Ceilings in Rigid Formats

Rigid containers are inherently designed for rotational and continuous-motion systems, which is why they scale so reliably at high speeds. Their fixed geometry allows containers to be indexed, accelerated, and decelerated with minimal positional variance, even at very high cycle rates.

Because the container does not deform, high-speed rotary fillers and seamers can operate with tight tolerances and minimal corrective logic. At the sealing point, the system is dealing with fewer variables: container shape is fixed, seal geometry is known, and contact pressure is mechanically controlled rather than thermally dependent.

Just as importantly, rigid containers have predictable mass and inertia. While they are heavier, their behavior under centrifugal forces is stable. Once a rigid line is tuned, it tends to stay tuned.

For this reason, rigid packaging lines commonly reach 300 to well over 1,000 units per minute, depending on container type and product characteristics.

Key insight: rigid packaging carries higher inertia, but it introduces far fewer surprises into a high-speed automated system.

Speed Ceilings in Flexible Formats

Flexible packaging often advertises high theoretical speed, but in practice, throughput is far more conditional.

Unlike rigid containers, flexible packages do not have inherent structural stability. Line speed becomes highly dependent on the consistency of the film itself, including thickness, stiffness, and surface properties. Even minor variation between film batches can affect how reliably pouches open, track, and seal.

Sealing parameters further constrain speed. Heat dwell time and temperature must remain within a narrow window, especially at higher speeds. Any product splash, dust, or oil migration into the seal area increases the risk of micro-leaks, forcing operators to slow the line or accept higher defect rates.

In addition, pouch opening and presentation accuracy becomes a critical bottleneck. If a pouch does not open cleanly or present consistently to the filler, the entire system must pause or reject the unit.

As a result, single-lane pouch machines typically cap at around 40 to 60 units per minute. To increase output, manufacturers do not accelerate the line; they add lanes. This approach increases mechanical complexity, expands factory footprint, and raises maintenance load, often faster than total throughput increases.

Key insight: flexible packaging scales by multiplication, not acceleration—and that distinction has major implications for cost, space, and reliability.

Changeovers, SKUs, and Line Flexibility

Modern food operations run more SKUs, more frequently, and with shorter production windows. In this environment, packaging format does not just influence flexibility—it determines whether that flexibility becomes an advantage or a liability.

Rigid packaging formats handle changeovers through physical tooling adjustments. Components such as star wheels, guide rails, and chucks must be removed, replaced, and mechanically realigned to accommodate a new container size or shape. These interventions increase downtime per changeover and require skilled technicians to execute correctly. As a result, rigid formats are best suited for long, stable production runs where container geometry remains constant for extended periods.

Flexible packaging formats approach changeovers very differently. SKU transitions are often managed digitally through stored recipes and servo-driven adjustments rather than mechanical part swaps. Bag width, seal timing, and gripper positioning can frequently be modified through the machine interface, reducing the need for physical change parts and enabling faster transitions between formats.

However, this flexibility comes with a tradeoff. Flexible systems are far more sensitive to incorrect setup. Small errors in tension, temperature, or timing that might go unnoticed in a rigid line can quickly translate into seal failures, misaligned pouches, or increased scrap. Fast changeovers amplify these risks when teams lack disciplined setup procedures or sufficient process maturity.

The reality: flexible packaging enables SKU agility, but it punishes poor discipline. The faster you change over, the more unforgiving the system becomes if parameters are not controlled with precision.

Labor, Handling, and Automation Readiness

Strip away the marketing language and focus on one thing: how much human intervention the system actually requires to keep running.

Rigid packaging formats tend to be inherently easier for automation to manage. Their fixed geometry allows robotic handling systems to grip, place, and transfer containers with high repeatability. Because containers behave predictably on conveyors and at transfer points, rigid lines typically require fewer manual corrections once they are tuned. Small variations in operator behavior—such as timing differences during restocking or minor misalignment during setup—are often absorbed by the system without triggering faults.

This tolerance makes rigid packaging more forgiving in real-world operating conditions, particularly in facilities where labor experience varies by shift or turnover is high. Once stabilized, rigid lines often run with minimal operator involvement beyond monitoring and replenishment.

Flexible packaging presents a different labor profile. While modern flexible systems can be highly automated, they are far less tolerant of inconsistency. If upstream processes are poorly designed or raw materials vary, flexible lines frequently require additional human intervention to correct film tracking issues, pouch opening failures, or sealing inconsistencies. These interventions may not stop the line entirely, but they accumulate as micro-stoppages that erode effective throughput.

Flexible packaging systems also place a higher dependency on trained operators. Correct setup, adjustment, and troubleshooting demand an understanding of tension control, sealing dynamics, and material behavior. Inexperienced teams can keep a flexible line running—but often at reduced speed or elevated scrap rates.

In facilities facing tight labor markets, high absenteeism, or frequent staff rotation, these differences matter. Under such conditions, rigid packaging formats often deliver more stable automation, not because they are more advanced, but because they demand less continuous human judgment to remain within tolerance.

Sealing, Shelf Life, and Failure Modes

This is where packaging decisions stop being theoretical and start showing up on financial statements.

Seal performance is not a quality “nice-to-have.” Under automation, it becomes a primary determinant of shelf life, recall risk, and downstream waste. The difference between rigid and flexible packaging is not simply how they seal, but how reliably those seals can be created, verified, and defended at speed.

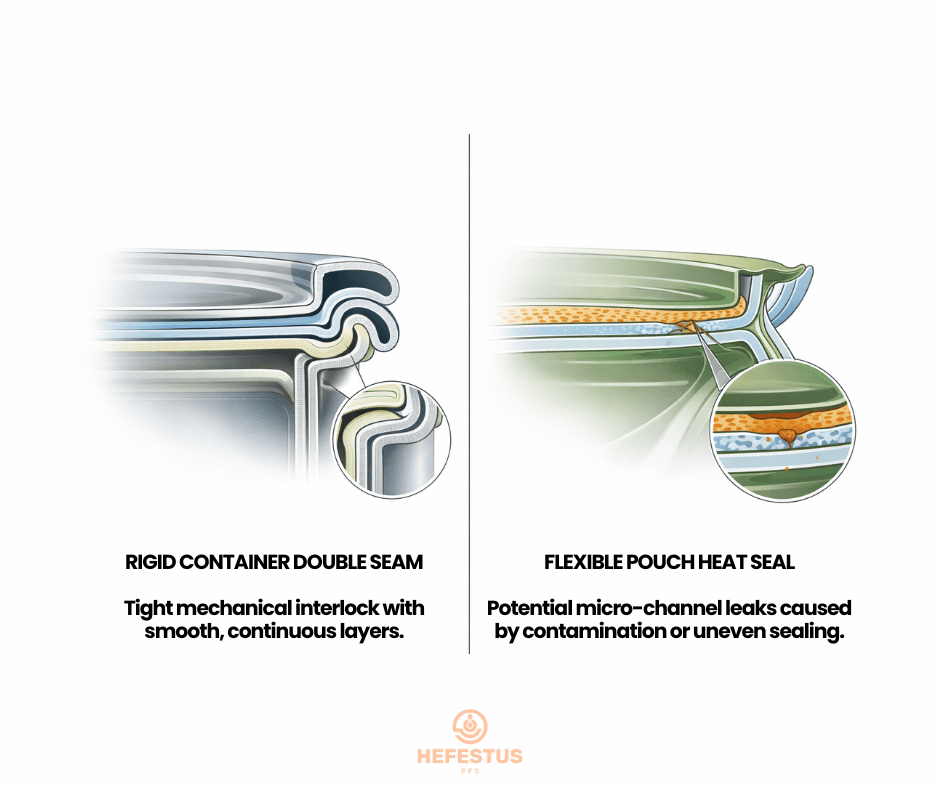

Seal Integrity Under Automation

Rigid packaging formats typically rely on mechanical or hybrid sealing systems, such as double seaming for cans or rigid containers combined with film or foil lids. These seals are formed through controlled mechanical force rather than thermal bonding alone. As a result, they are highly repeatable and, critically, measurable at production speed. Parameters such as seam thickness, overlap, and compression can be monitored inline, enabling rapid detection of defects before product leaves the line.

Flexible packaging relies almost entirely on heat sealing, a process governed by three interacting variables: time, temperature, and pressure. While modern heat sealing technology is sophisticated, it is inherently more sensitive to variation. Any contamination in the seal area—such as powder dust, oil residue, or product splash—can compromise seal integrity without producing an immediately visible defect.

These failures are rarely catastrophic at the point of production. Instead, they manifest later as micro-leaks, which are notoriously difficult to detect inline without specialized inspection systems. The cost does not appear as scrap on the line; it appears weeks later as spoilage, customer complaints, returns, or recalls.

From an automation perspective, the issue is not whether flexible packaging can seal effectively, but how narrow the acceptable operating window becomes as speed increases.

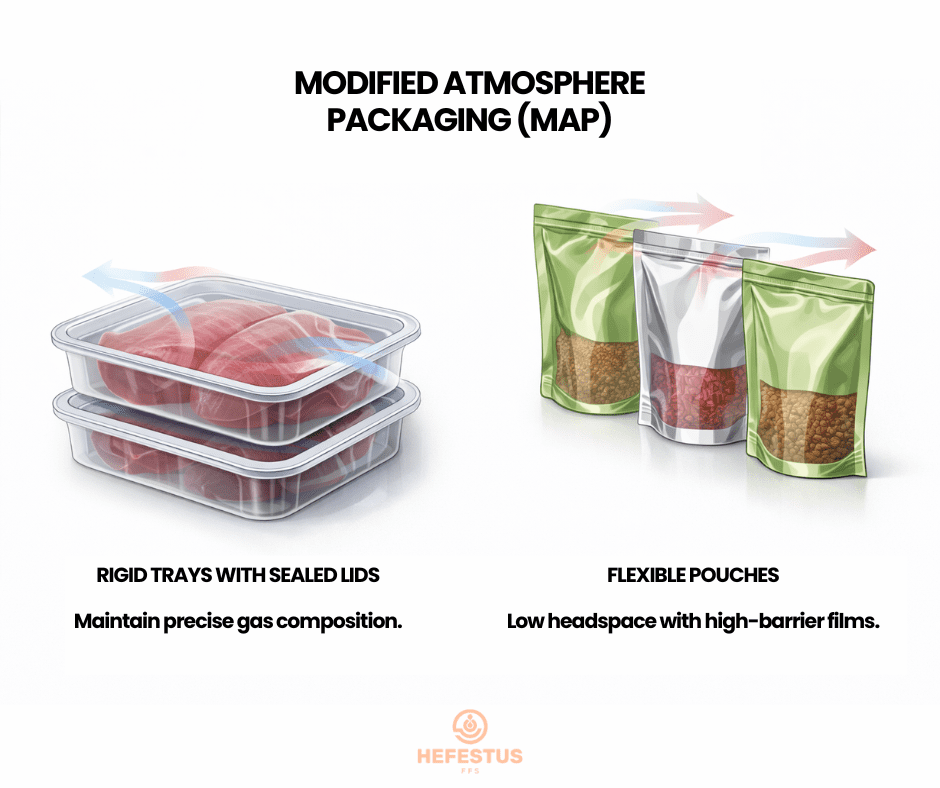

MAP Compatibility (Modified Atmosphere Packaging)

Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) adds another layer of complexity, and it further exposes the behavioral differences between rigid and flexible formats.

Rigid packaging excels in MAP applications where pressure control and headspace precision are critical. The structural stability of rigid containers allows gas composition and internal pressure to be tightly managed and maintained over time, making them well suited for products with long shelf-life requirements or high sensitivity to oxygen.

Flexible packaging performs exceptionally well in high-barrier, low-headspace applications, particularly where material efficiency and rapid evacuation are priorities. Advanced multi-layer films can provide excellent oxygen and moisture barriers when properly specified and processed.

However, both formats fail when MAP is misapplied. Products with incompatible respiration rates, moisture release, or biochemical activity will degrade regardless of packaging type if system parameters are poorly matched.

The decisive factor in MAP success is not the format itself, but system integration—the alignment of product behavior, gas composition, sealing method, and line control. Packaging format determines the boundaries of what is possible; integration determines whether those possibilities are realized or squandered.

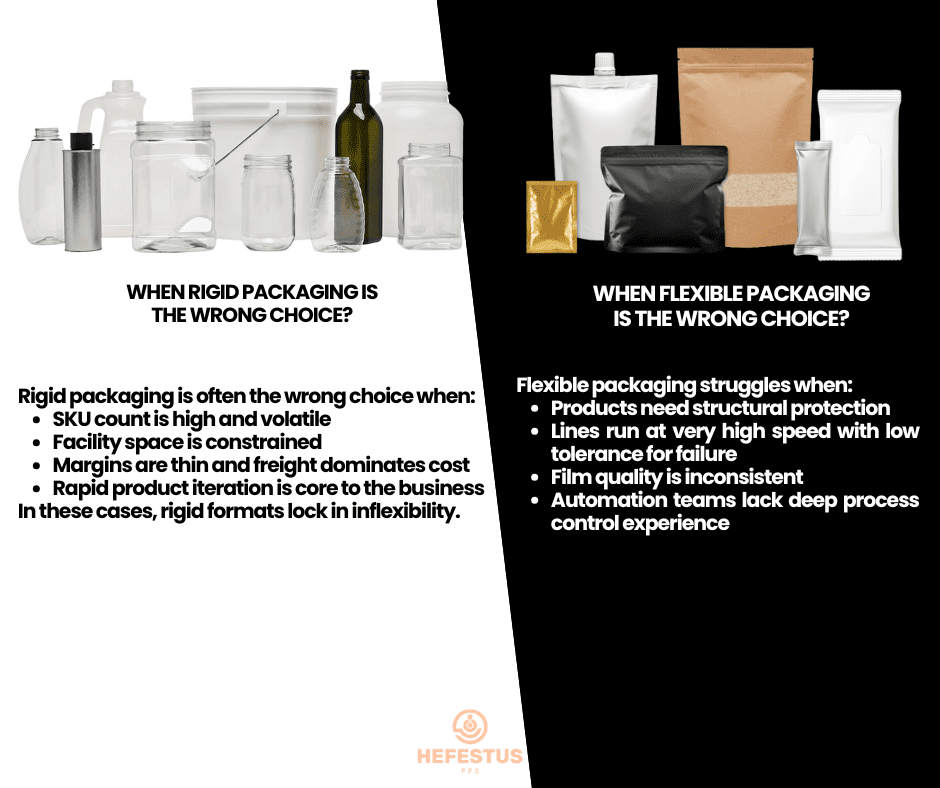

When Rigid Packaging Is the Wrong Choice

Saying this explicitly is not a weakness. It is what separates analysis from advocacy.

Rigid packaging is often the wrong choice in operations where SKU count is high and volatile. When formats, sizes, or product variations change frequently, the physical tooling required for rigid containers becomes a recurring source of downtime and friction. Each changeover reinforces inflexibility rather than efficiency.

Facility constraints also matter. Rigid packaging consumes space before filling, during storage, and across the production floor. In operations where floor space is limited or expansion is not feasible, rigid formats can quietly cap growth by locking throughput to physical layout.

Cost structure is another limiting factor. In low-margin categories where freight, warehousing, and handling dominate unit economics, the weight and volume of rigid containers amplify cost sensitivity. What looks manageable at small scale often becomes punitive as volume increases.

Finally, rigid packaging works against businesses where rapid product iteration is core to the model. When speed to market, frequent reformulation, or packaging experimentation drives competitive advantage, rigid formats impose a pace that the business may outgrow.

In these environments, rigid packaging does not fail dramatically—it fails structurally, by locking in inflexibility that the operation can no longer afford.

When Flexible Packaging Is the Wrong Choice

This is equally important—and far more often ignored.

Flexible packaging struggles when products require structural protection to survive handling, stacking, or long distribution chains. Without inherent rigidity, flexible formats rely heavily on secondary packaging and careful handling to prevent deformation or damage.

Flexible systems also become risky on very high-speed lines with low tolerance for failure. As throughput increases, the operating window for film quality, sealing conditions, and material consistency narrows. Small deviations that would be absorbed in slower systems quickly translate into defects or stoppages.

Film quality itself is a critical constraint. In environments where material supply varies, or where tight control over film specifications cannot be guaranteed, flexible packaging exposes the line to variability that automation is poorly equipped to absorb.

Perhaps most importantly, flexible packaging places heavy demands on process control maturity. Automation teams without deep experience in tension management, sealing dynamics, and material behavior often find themselves compensating with speed reductions, manual interventions, or elevated scrap.

In these conditions, flexible packaging does not deliver agility. It delivers increased downtime and operational risk, often masked by the assumption that “flexible equals simpler.”

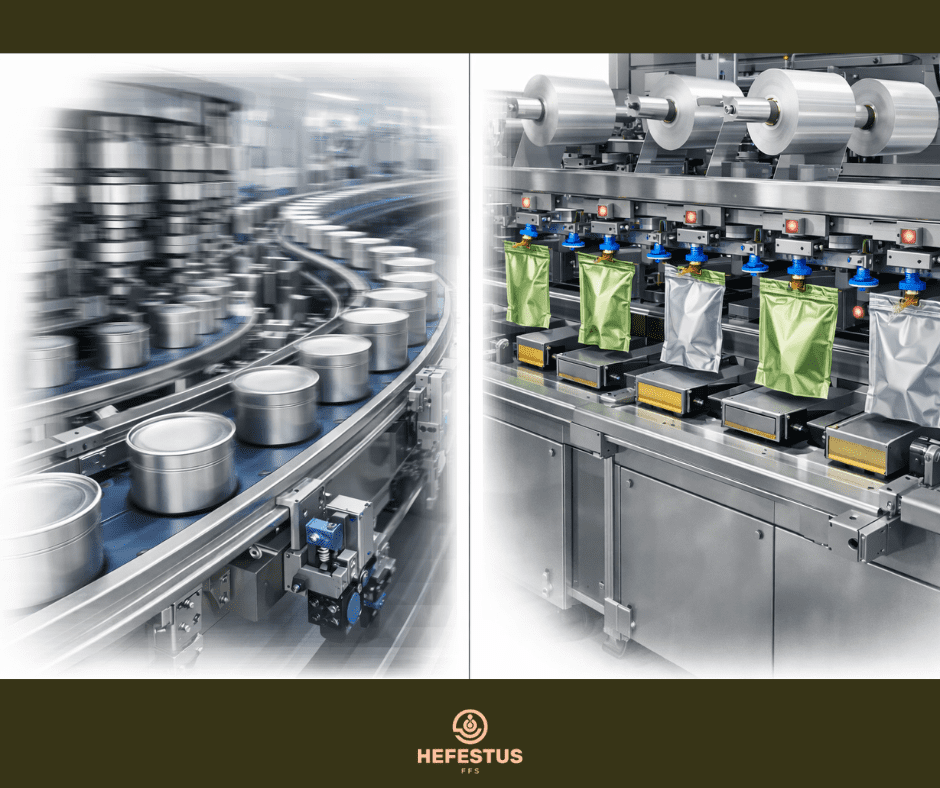

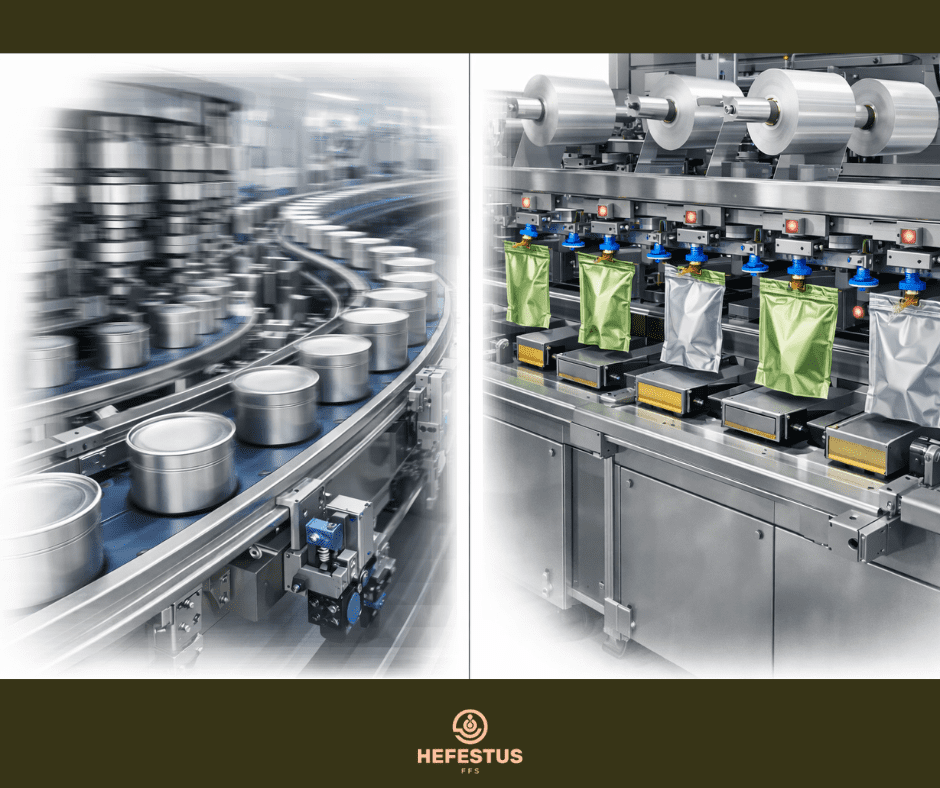

The Hybrid Reality: Rigid + Flexible Systems

The most advanced food automation lines do not choose sides in the rigid versus flexible debate. They combine formats deliberately.

Hybrid packaging systems exist because rigid and flexible formats solve different physical problems, and modern food production rarely benefits from solving only one of them. Where rigid packaging provides structural stability and predictable handling, flexible materials deliver barrier performance, material efficiency, and sealing versatility. Hybrids are the point where those advantages intersect.

In practice, this often takes the form of thermoformed bases paired with flexible lidding films. The rigid base ensures consistent orientation, stackability, and stability through filling and transport, while the flexible lid delivers high-barrier protection and efficient sealing. Cup fill-and-seal systems follow the same logic, using a rigid cup to stabilize handling and a flexible film to create a controlled seal.

Tray sealing with Modified Atmosphere Packaging is another common hybrid configuration. The rigid tray defines headspace geometry and protects the product mechanically, while the flexible film enables precise gas control and rapid sealing. This structure allows MAP systems to operate reliably at scale without demanding extreme tolerance from the film alone.

The reason hybrids dominate modern ready-meal, dairy, protein, and fresh food automation is simple: they allocate responsibility intelligently. Structural control is handled by rigid components. Barrier performance and material efficiency are handled by flexible films.

This balance allows producers to optimize control where it matters—during handling, transport, and indexing—while preserving efficiency where it counts, at the sealing and material level. Instead of forcing one format to compensate for its weaknesses, hybrid systems reduce overall system stress.

Hybrids are not a compromise. They are an acknowledgment that automation performs best when each material is asked to do what it is physically best suited to do.

How to Choose the Right Format for an Automated Line

This is a decision framework—not advice.

Ask these questions:

- What is the target throughput today and in three years?

- How volatile is the SKU mix?

- What is labor availability and skill depth?

- How constrained is factory footprint?

- How sensitive is the product to oxygen, moisture, or pressure?

- What future automation upgrades are planned?

Critical truth:

Packaging format decisions lock in automation paths for years. Reversing them is expensive and slow.

Final Takeaway: This Is a Production Decision, Not a Marketing One

The rigid vs flexible packaging debate is not about preference, aesthetics, or trend alignment. At its core, it is a choice between control and efficiency.

Rigid packaging prioritizes predictability. It favors stable geometry, repeatable motion, measurable seals, and throughput that holds as automation tightens. Flexible packaging prioritizes efficiency. It reduces material use, accelerates changeovers, and enables agility—but only within a narrower operating window that demands discipline and process maturity.

Neither approach is inherently better. Each simply fails in different ways.

The wrong packaging choice rarely collapses on day one. It degrades quietly. It shows up as unexplained downtime, creeping scrap rates, unstable throughput, or a line that cannot scale without constant human intervention. By the time those symptoms appear, the format decision has already hardened into the automation path.

That is why packaging format must be decided as a production architecture choice, not a marketing one. It determines how much variability your system can absorb, how much control your operators must exert, and how resilient your line will be under pressure.

Choose based on how your operation behaves at scale—not how your product looks at launch.