Why Packaging Lines Fail

Most packaging lines don’t fail because someone bought the wrong machine.

They fail because the line was designed to look good on paper—not to survive real production.

That’s the uncomfortable reality manufacturers discover after commissioning, when quoted speeds collapse, changeovers explode, and operators spend more time managing exceptions than making product.

This guide explains why packaging lines fail, drawing on real-world operations, engineering constraints, and system-level mistakes that quietly destroy throughput. You’ll learn where failure actually starts—and how to prevent it before it costs you uptime, margin, and credibility.

Failure #1 — Designing for Peak Speed, Not Real Throughput

Most packaging machines are sold on a single number: units per minute.

That number is almost always misleading.

Quoted speeds are generated under idealized conditions that rarely — if ever — exist on a production floor. They assume uninterrupted operation, perfectly conditioned product, and a line running indefinitely without human or process intervention. In other words, they describe what a machine can do in isolation, not what a packaging line will do in reality.

Typically, quoted speeds assume:

- Ideal, uninterrupted product flow

- Continuous operation with no sanitation or cleaning pauses

- No seal dwell or cooling constraints

- Perfect upstream feeding with zero variability

None of these conditions hold in live production environments.

In real facilities, sustained throughput is shaped by a very different set of forces — most of which are invisible during purchasing decisions:

- Fill accuracy adjustments to stay within weight tolerances

- Seal dwell time, especially when using films or MAP configurations

- In-process quality checks that interrupt continuous motion

- Short but frequent sanitation or cleaning stops

- Operator intervention to correct drift, jams, or misfeeds

Each of these factors trims seconds from every minute. Individually, they seem insignificant. Collectively, they define your true output.

That’s why a line rated at 120 units per minute often stabilizes closer to 70–85 units per minute once real constraints appear. This isn’t a commissioning failure or an operator issue. It’s the natural outcome of designing around peak speed instead of operational reality.

Key insight:

Peak speed is a marketing metric. Sustained speed is a design metric.

If sustained throughput isn’t modeled from the start, the gap between expectation and performance is guaranteed.

Failure #2 — Mismatch Between Product Behavior and Machine Design

Products do not behave consistently — and most packaging machines are not designed to adapt once variability appears.

During specification and factory acceptance testing, products are often treated as static. Viscosity is assumed to be stable. Flow is assumed to be predictable. Density is assumed to remain within narrow bands. Under those assumptions, many machines perform flawlessly.

Production reality breaks those assumptions quickly.

As soon as a line runs for extended periods, product behavior begins to drift. Temperature rises. Shear changes viscosity. Solids separate or settle. Gas release increases foaming. What looked stable during trials becomes dynamic on the floor.

The most common product-driven failure modes include:

- Viscosity drift caused by temperature changes, shear, or settling over time

- Particulates that bridge, clog, or separate during extended runs

- Foaming introduced by filling velocity, entrained air, or agitation

- Density changes between batches or within a single production run

Machines that rely on narrow operating windows struggle once these shifts occur. They compensate temporarily through operator adjustments, but those adjustments introduce instability elsewhere in the line.

Most validation fails to catch this because it happens under the wrong conditions.

Equipment is typically tested with lab samples or short-duration trials. These tests confirm that the machine can run the product — not that it can run it reliably over time. Once production begins, several realities emerge:

- Product is warmer than during testing

- Run times extend from minutes to hours

- Upstream conditions fluctuate as tanks empty and refill

That’s why packaging lines that “ran perfectly during FAT” often destabilize weeks later. The machine didn’t degrade — the assumptions did.

Why lab tests fail:

They do not model time, variability, or fatigue — the three forces that dominate real production.

Key insight:

If a packaging line is not validated using actual production product under sustained conditions, failure is delayed, not avoided.

Failure #3 — Poor Integration Between Filling, Sealing, and Conveying

Packaging line stability is dictated by flow logic, not by the individual performance of machines.

A filler, sealer, or conveyor can each operate exactly as specified and still fail together if the line is not designed as a single, coordinated system. Most integration failures don’t show up as dramatic breakdowns. They show up as instability — subtle, persistent, and expensive.

The most common integration errors include:

- Push systems feeding pull processes, forcing downstream equipment to absorb variability

- No true accumulation strategy, leaving the line brittle instead of resilient

- Mismatched response times between modules that react to disturbances at different speeds

These issues rarely cause hard stops. Instead, they create micro-stoppages — short interruptions lasting two to ten seconds that feel insignificant in isolation. Over the course of a shift, they quietly erode performance.

OEE practitioners consistently report that frequent short stops account for 30–50% of lost availability, even on lines that experience few major breakdowns. Because the line appears to be “running,” the loss often goes unchallenged.

This is why push versus pull architecture is not an academic debate.

Flow logic determines how disturbances propagate through the line. A poorly matched push–pull relationship directly affects:

- Pressure applied to seals during downstream slowdowns

- Product slosh and spillage during acceleration and deceleration

- Film tracking stability under fluctuating tension

- Jam frequency at transfer points and infeed zones

When flow is mismanaged, the line compensates continuously — through sensors, stops, and operator intervention. That compensation masks failure while steadily reducing output.

Key insight:

A packaging line that “never fully stops” can still be failing.

If integration is not designed deliberately, instability becomes the default operating mode.

Failure #4 — Changeover Was an Afterthought

SKU creep kills more packaging lines than mechanical breakdowns ever will.

Most lines are designed around a small number of “core” products. Then commercial reality sets in. Marketing adds variants. Sales pushes customization. Retailers demand differentiation. Each request seems incremental and justified.

Collectively, they reshape the line into something it was never designed to handle.

Every additional SKU introduces operational friction. Not once—but every time the line switches. That friction shows up as:

- Tooling swaps that require mechanical adjustment and verification

- Height and width changes across guides, rails, and sensors

- Recipe changes that alter fill behavior, sealing parameters, or gas flush timing

- Cleaning and sanitation resets that interrupt production entirely

On paper, these steps look manageable. In reality, they stack.

Most ROI models assume:

- Ideal changeover times

- Perfect operator execution

- No revalidation or trial runs

- Minimal quality fallout after restart

Those assumptions don’t survive contact with production.

In practice, changeovers routinely take two to four times longer than modeled. Adjustments cascade across the line. First-run rejects increase. Operators slow the line to stabilize it. What was budgeted as a minor interruption becomes a recurring tax on throughput.

When sanitation is involved—as it is in food, beverage, and pharmaceutical environments—the cost multiplies even faster. Cleaning isn’t just downtime; it resets thermal conditions, product behavior, and machine state. The line doesn’t resume where it left off. It has to be rebuilt operationally, every time.

Over a week or month, these “small” overruns compound into lost shifts, missed volumes, and eroded margins.

Key insight:

A packaging line optimized for one SKU is fragile by definition.

If changeover complexity is not treated as a primary design constraint from the start, the line will eventually collapse under its own flexibility.

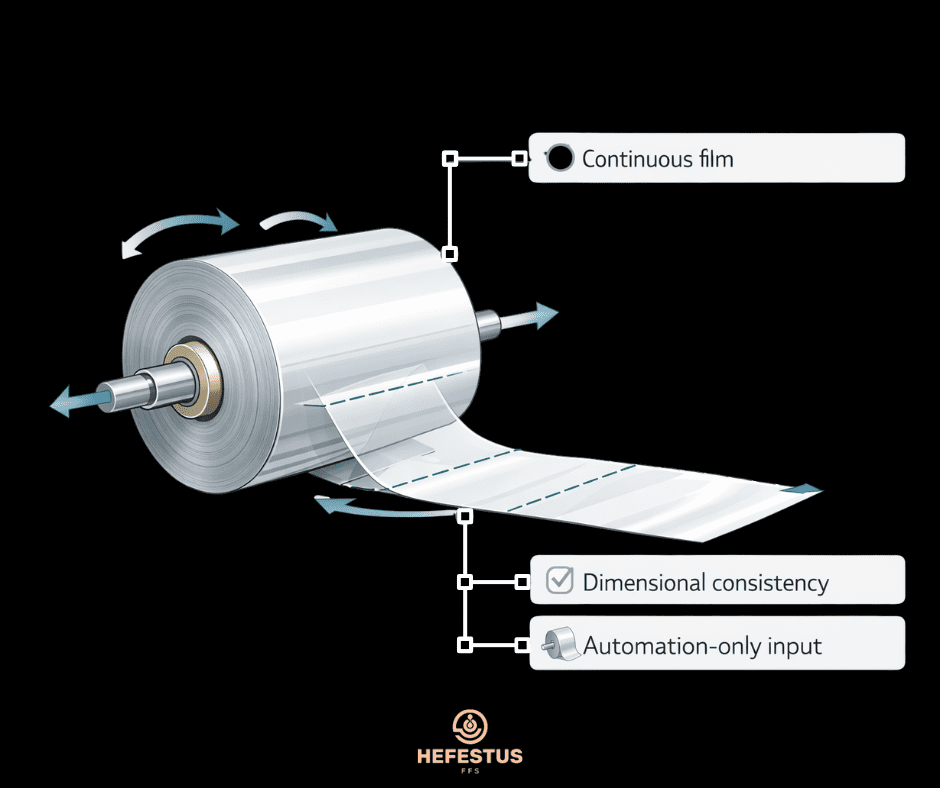

Failure #5 — MAP and Sealing Constraints Set the Real Ceiling

In many packaging lines, sealing — not filling — ultimately defines maximum throughput.

Filling is visible. Sealing is not. That’s why teams often focus their optimization efforts upstream, only to discover later that no amount of filling speed can overcome sealing physics.

Sealing is constrained by time, energy transfer, and material behavior. Those constraints don’t scale linearly with speed.

With standard sealing, the margin for error is already narrow. With Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP), it becomes non-negotiable.

MAP improves shelf life by controlling the internal gas composition of a package. But gas exchange takes time. Heat transfer takes time. Seal formation takes time. None of these can be compressed indefinitely without consequences.

The fundamental constraints include:

- Gas flushing requires dwell time to displace oxygen effectively

- Film type dictates heat transfer limits, regardless of machine power

- Seal integrity degrades at higher speeds, even when seals appear acceptable

- Leak rates increase before visible defects appear, masking failure at the machine

These are not tuning issues. They are physical limits.

Many teams only realize this after commissioning, when attempts to increase speed produce unintended results. The line appears stable. Packages look fine. But shelf-life performance erodes. Leak rates rise. Customer complaints appear weeks later — far downstream from the sealing station.

That delay is what makes sealing failures so costly.

As a result, teams often discover too late that:

- The sealer, not the filler, is the true bottleneck

- Speed increases directly compromise shelf life

- Quality failures emerge in distribution, not on the factory floor

By the time the problem is visible, thousands of units may already be in the market.

Key insight:

If sealing performance is not modeled first, everything upstream is theoretical.

A packaging line can only run as fast as its seals can reliably form — not as fast as its filler can dispense.

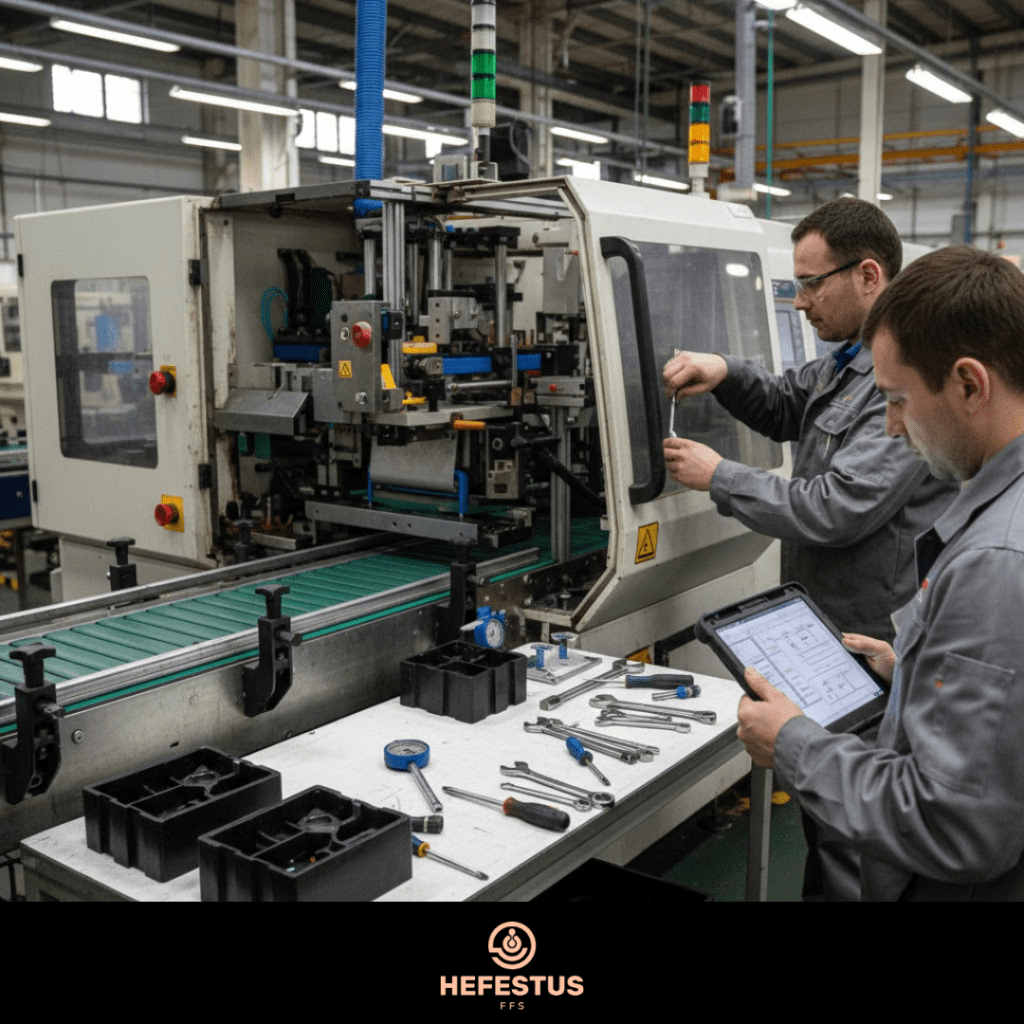

Failure #6 — Compact Footprints Create Hidden Constraints

“Space-saving” packaging line layouts often look efficient on drawings. On the production floor, they frequently trade square meters for uptime.

Compact footprints are usually driven by real pressures: limited floor space, high real-estate costs, or the desire to future-proof capacity. But when layout decisions prioritize density over access, they introduce constraints that don’t show up until the line is live.

Most footprint-driven failures are not catastrophic. They are persistent.

Common issues created by overly compact layouts include:

- Limited access for cleaning, inspection, and sanitation

- Poor visibility for adjustments, fault diagnosis, and verification

- Overlapping service zones where one task blocks another

- Vertical stacking of maintenance tasks, forcing sequential work instead of parallel intervention

None of these stop the line outright. Instead, they slow every response.

Tight layouts increase the mean time to repair (MTTR) because simple interventions require partial disassembly, awkward reach, or safety lockouts. They also increase safety risk, as operators work closer to moving equipment or hot sealing surfaces. Over time, they create operator hesitation — not because teams are untrained, but because access is inconvenient and consequences feel higher.

What looks compact and elegant in CAD often becomes restrictive and fragile in operation.

These constraints are especially damaging in areas already sensitive to stability, such as sealing stations, accumulation zones, and changeover points. When access is limited, small issues persist longer. When visibility is poor, drift goes unnoticed. When tasks stack vertically, recovery slows.

The result is not more breakdowns — it’s more lost minutes.

Key insight:

Every square meter you save carries an operational price.

If layout decisions do not explicitly account for access, adjustment, and recovery time, uptime will be sacrificed to density.

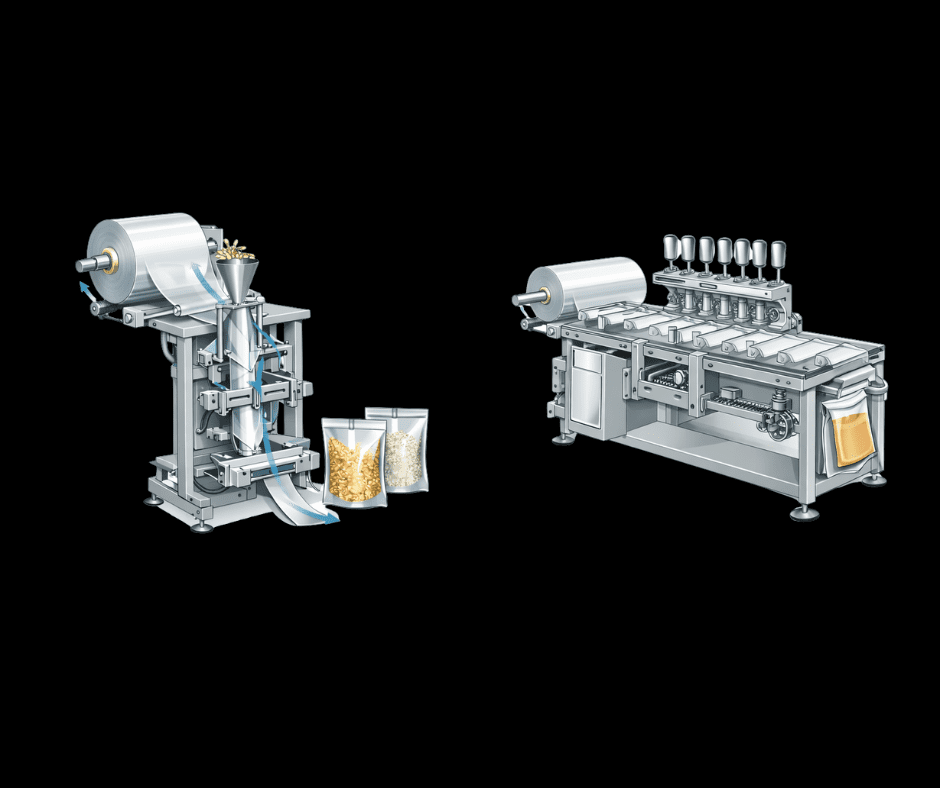

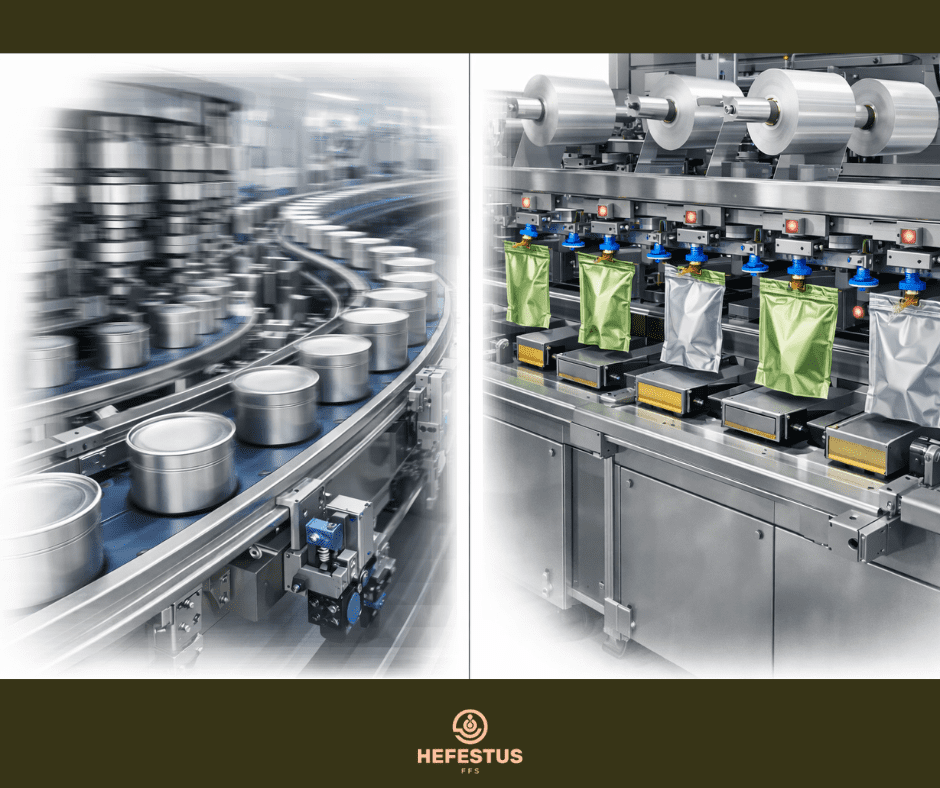

Failure #7 — Buying Machines Instead of Systems

This is the failure most teams miss — and the one that makes all the others inevitable.

Packaging lines fail when companies purchase excellent individual machines and assume they will behave like a system. On paper, this approach looks rational. Each component is best-in-class. Each vendor has strong references. Each machine performs as specified in isolation.

In practice, that assumption breaks down almost immediately.

Packaging lines built from disconnected point solutions rely on informal coordination rather than unified architecture. Each machine optimizes its own performance, responding to disturbances locally instead of stabilizing the line globally.

Most failures begin the moment variability enters the system.

Companies typically buy:

- Best-in-class fillers

- Best-in-class sealers

- Best-in-class conveyors

…and expect them to work together.

Without a shared control philosophy, common performance targets, and clearly defined interfaces, they rarely do.

The symptoms are predictable:

- Finger-pointing between vendors when performance targets aren’t met

- Integration delays as responsibility for tuning falls between contracts

- Ownership gaps where no one is accountable for end-to-end behavior

- Local optimization that improves one module while destabilizing another

Each vendor tunes their equipment to protect their scope. No one tunes the system to protect throughput.

This is why lines assembled from high-quality components can still underperform badly. The problem is not competence. It’s fragmentation.

Point solutions optimize themselves.

Systems optimize outcomes.

A system requires:

- Unified architecture and flow logic

- Clearly defined ownership of overall performance

- Shared assumptions about variability, recovery, and limits

- Design decisions made for the line, not the machine

Without these, integration becomes reactive and fragile, and the line never truly stabilizes.

Key insight:

A packaging line is only as strong as its weakest interface.

When responsibility stops at the machine boundary, failure migrates to the gaps between them.

How to Prevent Packaging Line Failure Before It Happens

Preventing packaging line failure isn’t about better troubleshooting after commissioning. It’s about making the right decisions before the first machine is ordered.

Here is a decisive, system-level checklist used by teams that build stable, scalable packaging lines — not just fast ones.

Design for Sustained Speed

Model realistic throughput, not peak ratings.

Peak speed describes what a machine can do under ideal conditions. Sustained speed defines what a line will deliver shift after shift. If throughput is not modeled with downtime, variability, and recovery built in, performance gaps are guaranteed.

Validate With Real Product

Not samples. Not short trials. Production reality only.

Validation must reflect actual temperature, viscosity drift, particulates, run duration, and upstream variability. Anything less confirms possibility — not reliability.

Model Changeover and Sanitation Time

If it isn’t in the ROI, the ROI is fiction.

Changeovers, cleaning, and revalidation don’t just pause production — they reset system stability. Ignoring them in economic models guarantees missed targets later.

Integrate Filling, Sealing, and Conveying

Treat flow as one system, not a series of handoffs.

Push vs pull logic, accumulation strategy, and response timing must be designed together. Integration cannot be “sorted out later” without sacrificing OEE.

Let Sealing Define the Ceiling

Everything upstream must support it.

Sealing physics set non-negotiable limits on speed, dwell, and quality — especially with MAP. If sealing isn’t modeled first, throughput assumptions are theoretical.

Design for Access, Not Just Footprint

Maintenance speed is uptime.

Layouts must support visibility, adjustment, cleaning, and recovery. Compact designs that restrict access trade density for downtime.

Buy Architecture, Not Components

Ownership of performance must be unified.

Individual machines don’t fail — interfaces do. Without shared architecture and clear accountability for line-level behavior, even best-in-class equipment underperforms.

The Pattern Behind All Packaging Line Failures

Packaging lines don’t fail because teams are careless or operators are undertrained.

They fail because systems thinking is skipped in favor of local optimization.

When design decisions prioritize speed over stability, components over architecture, and drawings over operations, failure is not accidental — it is engineered in.

Conclusion

Packaging lines don’t fail because teams are careless.

They fail because systems thinking is skipped.

When you look closely at why packaging lines fail, the pattern is consistent: speed is modeled instead of sustained throughput, product behavior is assumed to be static, changeover and sanitation are underestimated, sealing limits are discovered too late, and machines are bought as components instead of as part of a unified system.

Most breakdowns are predictable. Most downtime is designed in. And most “bad machines” are simply placed into impossible systems.

Design for reality—not brochures—and you don’t just avoid failure. You build packaging lines that scale.

If this guide clarified what’s really breaking packaging performance, consider sharing it with your operations or engineering team—or explore more insights from Hefestus on designing packaging lines that work in the real world.